OPINION: We moved abroad, but we should still get our vote

People living abroad often retain strong links to their home countries. They should also get a vote, argues James Savage.

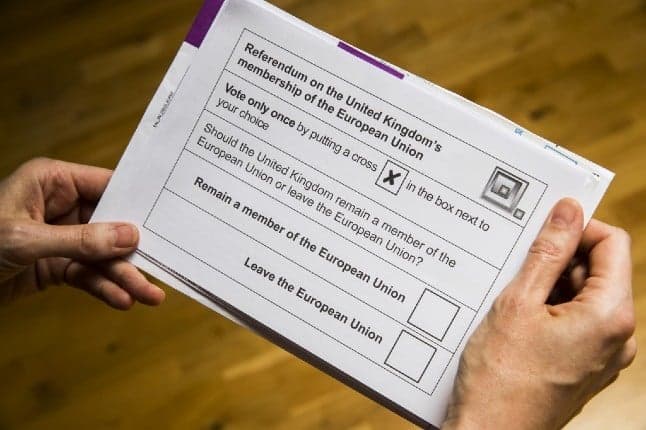

It was the way he put it: ’You cut the cord when you left this country’. Him: Brian, a total stranger. The subject: Brexit. The forum: a discussion under a Facebook post by a friend of mine back home in England, just before the 2016 referendum. His point: that the likes of me shouldn’t have a vote.

In a sense it’s easy to see his point. I don’t live in Britain, I live and pay my taxes in Sweden. I don’t use Britain’s National Health Service, its schools or its roads. I don’t have a British pension to speak of. Lots of the issues that affect Brits don’t affect me, even if Brexit itself affects Brits living in the EU like me far more personally than it affects most Brits living in the UK.

Before you switch off, this isn’t another article about Brexit, nor is it just about Brits abroad. There’s a bigger question here: should any of us who live abroad get a say in how they run the countries we left behind?

Countries deal with this conundrum in different ways. Ireland is among the strictest: if you are not resident in Ireland, you don’t get to vote (though there are moves afoot to change this). Brits keep the vote for fifteen years after leaving, Australians keep it for six years.

France and the US keep it simple: if you’re a citizen, you get the vote. France even has special deputies who represent expats. All Swedish citizens get a vote as long as they have at some point in their lives lived in Sweden. I looked up the rules for Germany too (well, let’s just say it’s… complicated).

But what’s fair? Should people get a say in a country that they don’t live in?

A British opposition lawmaker called Margaret Hodge angered many this week when she criticised government plans to remove the country’s 15-year rule. It would give tax exiles the vote, she fumed, adding: “If you stop paying your taxes in to the system, you should have no right to a vote.”

There are quite a lot of things to say about this, firstly that we’re on a dangerous path if we start to link paying tax to the right to vote –– many voters, like people on low incomes, don’t pay tax. But also that of the millions of people who live outside their home countries, Brits and others, very few are doing it to dodge the taxman. Also, if Hodge is worried that extending the franchise will favour Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, maybe she shouldn’t be. Some on the French left opposed the creation of overseas constituencies for this reason, but in reality the centre and left have won more seats through the system than the right.

People move abroad for many reasons: to work, to follow loved ones, to retire, on a whim. While some become entirely integrated into their new homes, very few of us cut the cord entirely, whatever my Facebook interlocutor Brian thinks. Some left as teenagers, but some spent an entire working life paying into the system, and many live on a pension from home. Some are employed on an expat contract and pay taxes at ‘home’, despite living abroad. Some keep property or run businesses there. And sometimes, issues arise that deeply affect our lives, whether that’s big constitutional changes like Brexit or questions like migration rights for families.

And we keep in touch: most of us follow the news from home to some extent, and whether we like it or not, we all become unofficial ambassadors for our home countries, trying to explain their politics, culture and eccentricities. This has been a busy few years for Brits abroad, and I dare say Americans too.

Some argue that nonetheless you should vote where you live. This is an attractive argument –– personally I cast my vote in Sweden and am satisfied with that. But Sweden makes this easy, and for people in many countries this is not an option. To vote in national elections you almost always need to be a citizen, and becoming a citizen can be hard, especially if you live somewhere like Spain that doesn’t recognise dual citizenship. The result is millions of people born in democracies and living in democracies having similar voting rights to Saudi Arabian women. If some people end up voting twice, is that worse than the current situation where many get no vote at all?

If there’s a problem with voting it’s that too few people do it, rather than too many. And extending the vote can help build a global network of civilly engaged citizens, forging links between the places they left and the places they live. Governments everywhere would do well to see their citizens abroad as a resource, and give them the rights that citizens are due.

Comments (4)

See Also

It was the way he put it: ’You cut the cord when you left this country’. Him: Brian, a total stranger. The subject: Brexit. The forum: a discussion under a Facebook post by a friend of mine back home in England, just before the 2016 referendum. His point: that the likes of me shouldn’t have a vote.

In a sense it’s easy to see his point. I don’t live in Britain, I live and pay my taxes in Sweden. I don’t use Britain’s National Health Service, its schools or its roads. I don’t have a British pension to speak of. Lots of the issues that affect Brits don’t affect me, even if Brexit itself affects Brits living in the EU like me far more personally than it affects most Brits living in the UK.

Before you switch off, this isn’t another article about Brexit, nor is it just about Brits abroad. There’s a bigger question here: should any of us who live abroad get a say in how they run the countries we left behind?

Countries deal with this conundrum in different ways. Ireland is among the strictest: if you are not resident in Ireland, you don’t get to vote (though there are moves afoot to change this). Brits keep the vote for fifteen years after leaving, Australians keep it for six years.

France and the US keep it simple: if you’re a citizen, you get the vote. France even has special deputies who represent expats. All Swedish citizens get a vote as long as they have at some point in their lives lived in Sweden. I looked up the rules for Germany too (well, let’s just say it’s… complicated).

But what’s fair? Should people get a say in a country that they don’t live in?

A British opposition lawmaker called Margaret Hodge angered many this week when she criticised government plans to remove the country’s 15-year rule. It would give tax exiles the vote, she fumed, adding: “If you stop paying your taxes in to the system, you should have no right to a vote.”

There are quite a lot of things to say about this, firstly that we’re on a dangerous path if we start to link paying tax to the right to vote –– many voters, like people on low incomes, don’t pay tax. But also that of the millions of people who live outside their home countries, Brits and others, very few are doing it to dodge the taxman. Also, if Hodge is worried that extending the franchise will favour Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, maybe she shouldn’t be. Some on the French left opposed the creation of overseas constituencies for this reason, but in reality the centre and left have won more seats through the system than the right.

People move abroad for many reasons: to work, to follow loved ones, to retire, on a whim. While some become entirely integrated into their new homes, very few of us cut the cord entirely, whatever my Facebook interlocutor Brian thinks. Some left as teenagers, but some spent an entire working life paying into the system, and many live on a pension from home. Some are employed on an expat contract and pay taxes at ‘home’, despite living abroad. Some keep property or run businesses there. And sometimes, issues arise that deeply affect our lives, whether that’s big constitutional changes like Brexit or questions like migration rights for families.

And we keep in touch: most of us follow the news from home to some extent, and whether we like it or not, we all become unofficial ambassadors for our home countries, trying to explain their politics, culture and eccentricities. This has been a busy few years for Brits abroad, and I dare say Americans too.

Some argue that nonetheless you should vote where you live. This is an attractive argument –– personally I cast my vote in Sweden and am satisfied with that. But Sweden makes this easy, and for people in many countries this is not an option. To vote in national elections you almost always need to be a citizen, and becoming a citizen can be hard, especially if you live somewhere like Spain that doesn’t recognise dual citizenship. The result is millions of people born in democracies and living in democracies having similar voting rights to Saudi Arabian women. If some people end up voting twice, is that worse than the current situation where many get no vote at all?

If there’s a problem with voting it’s that too few people do it, rather than too many. And extending the vote can help build a global network of civilly engaged citizens, forging links between the places they left and the places they live. Governments everywhere would do well to see their citizens abroad as a resource, and give them the rights that citizens are due.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.